The Grim Blade of Justice – The Guillotine’s Reign in Revolutionary France and the Terrors It Unleashed

Origins and Historical Context

Predecessor Devices

Before the guillotine’s introduction in France, similar execution devices existed across Europe. From the 13th century, the Halifax Gibbet in England was used to execute thieves whose stolen goods exceeded a certain value. Similarly, the Maiden in Scotland, constructed in 1564, operated on the principle of decapitation by a falling blade. These devices were typically reserved for the nobility, as beheading was considered a more “humane” punishment compared to hanging or burning, which were common for the lower classes.

The Birth of the Guillotine in France

In 1789, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a member of the French National Assembly, proposed the use of a mechanized execution device to ensure equality in the administration of the death penalty. Prior to the French Revolution, nobles were typically beheaded with a sword or axe, while commoners endured more brutal methods like hanging or breaking on the wheel. Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers such as Cesare Beccaria, Guillotin sought a swift, less painful method applicable to all social classes.

The guillotine was designed by Dr. Antoine Louis, with contributions from German engineer Tobias Schmidt. After trials on animals and corpses at Bicêtre Hospital, the device was first used on April 25, 1792, to execute highwayman Nicolas-Jacques Pelletier at Place de Grève in Paris. Initially called the “louisette” or “louison” after Antoine Louis, it eventually became known as the “guillotine,” much to Guillotin’s dismay.

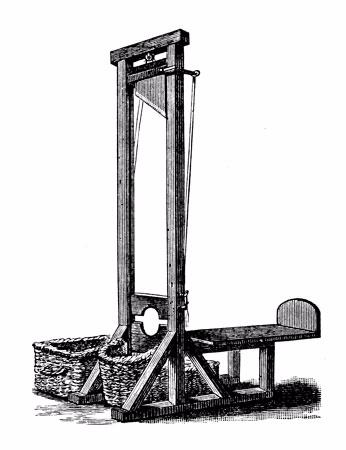

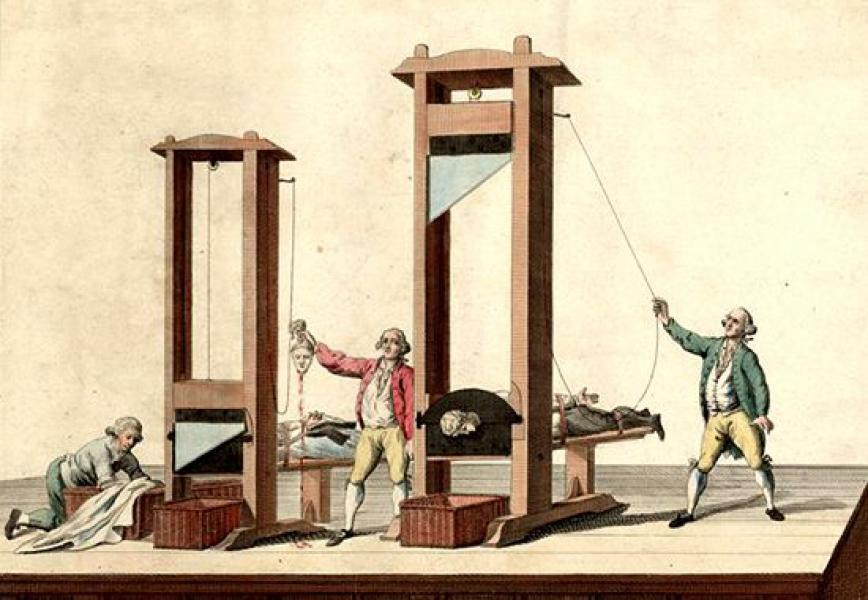

Design and Mechanism

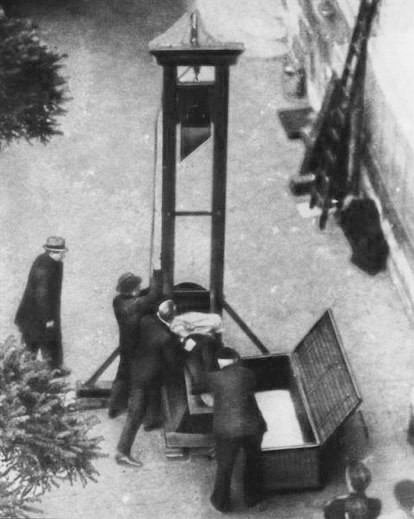

The guillotine consisted of two vertical posts, approximately 4.3 meters tall, connected by a crossbeam. A weighted blade, initially straight but later angled for greater efficiency, was suspended at the top, weighing around 40 kilograms and dropped via a rope-and-pulley system. The victim was positioned face-down, with their neck secured in a wooden frame (lunette), and the blade severed the head in a fraction of a second. This design ensured a near-instantaneous death, minimizing suffering compared to earlier methods.

Archaeological and Cultural Significance

A Symbol of Equal Justice

The guillotine was introduced as a symbol of Enlightenment ideals, embodying the French Revolution’s motto of “liberté, égalité, fraternité” (liberty, equality, fraternity). By applying a single method of execution to all social classes, it broke with the tradition of class-based punishments. However, this humanitarian intent was quickly overshadowed as the guillotine became a tool of mass political violence during the Reign of Terror.

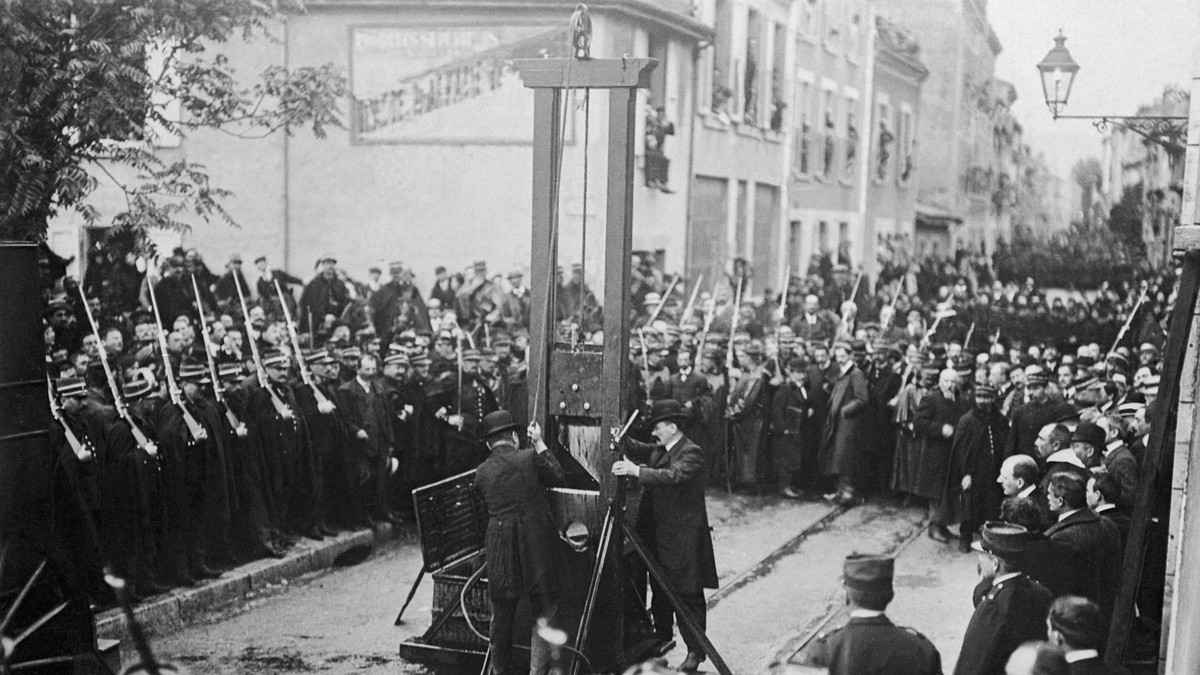

A Symbol of Terror

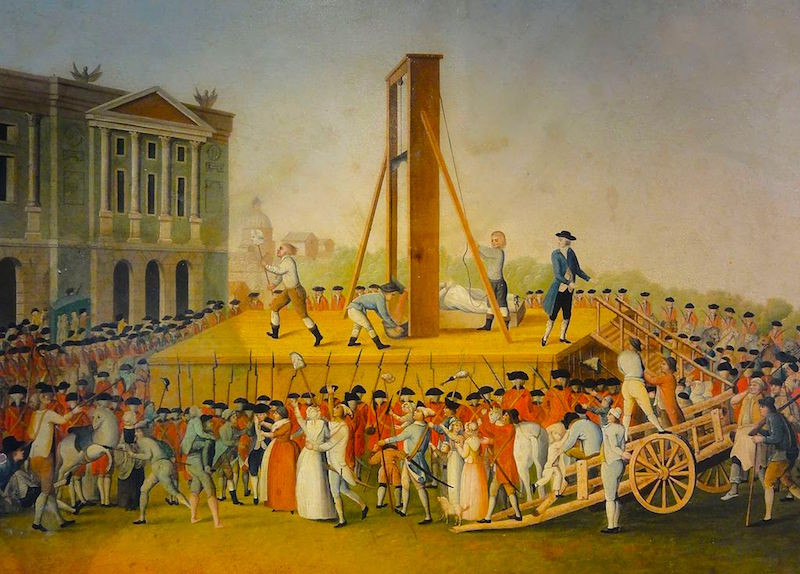

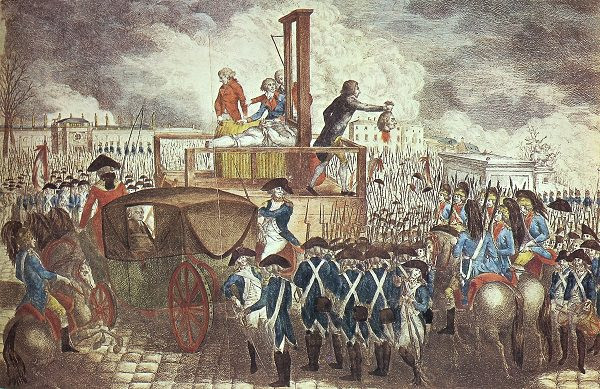

During the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), the guillotine became synonymous with brutality and revolutionary justice. Estimates suggest 17,000 to 40,000 people, including King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre, were executed. Public executions at Place de la Révolution (now Place de la Concorde) drew large crowds, turning death into a form of public entertainment. Women known as “Tricoteuses” famously knitted beside the scaffold, while spectators purchased programs listing victims’ names and dined at establishments like the “Cabaret de la Guillotine.”

Long-Term Impact

The guillotine’s use extended beyond France. During the Nazi regime, approximately 16,500 individuals, primarily resistance fighters and political opponents, were executed by guillotine in Germany from 1933 to 1945. In France, it remained the official method of execution until the death penalty was abolished in 1981. The last person executed by guillotine was Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian murderer, in 1977.

Notable Examples

Execution of Louis XVI (January 21, 1793): Deposed and convicted of treason, Louis XVI was one of the guillotine’s most famous victims. His execution marked the end of absolute monarchy in France and solidified the power of the revolutionary government. Historical accounts note that Louis XVI proclaimed his innocence until the end.

Execution of Marie Antoinette (October 16, 1793): Queen Marie Antoinette, dubbed “Madame Deficit” for her extravagant lifestyle, was convicted of treason and executed nine months after her husband. Her death sparked widespread controversy and symbolized public rage against the aristocracy.

Execution of Maximilien Robespierre (July 28, 1794): A key architect of the Reign of Terror, Robespierre was himself guillotined after being declared an outlaw by his fellow revolutionaries. His death marked the end of the Terror, though the revolution continued.

Use During Nazi Germany: Under Hitler’s regime, the guillotine was widely used to execute political opponents and resistance members. The estimated 16,500 victims highlight its role not only in the French Revolution but also in later authoritarian regimes.

Archaeological Analysis

The Artifact’s Role in History

From an archaeological perspective, the guillotine is a significant artifact, reflecting the intersection of technology, politics, and culture. Its simple yet effective design showcases technical advancements of the Enlightenment era, while its widespread use in public executions reveals shifting societal views on justice and violence. Physical relics, such as a guillotine blade from Guadeloupe (now housed at the Royal Museums Greenwich), provide tangible evidence of its global reach.

Symbolic Significance

The guillotine is a paradoxical symbol: it represents both equal justice and extreme violence. Engravings and drawings from the French Revolution, such as “Robespierre guillotinant le boureau” (1794), illustrate how the guillotine was used to convey political and social messages. In the diary of Céléstin Guittard de Floriban, simple sketches of the guillotine and its victims reflect the fear and resignation of the populace during the Terror.

Legacy and Controversy

Despite its humanitarian origins, the guillotine became a tool of political repression. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was so distressed by its association with brutality that his family changed their surname to distance themselves from it. Today, the guillotine remains a potent symbol in political protests worldwide, from Spain to the United States, representing discontent with social injustice.

Conclusion

The guillotine is a unique archaeological artifact, notable not only for its technical design but also for its role in shaping history and culture. From a device intended to ensure equal justice, it became an emblem of violence and terror during the French Revolution and beyond. Examples such as the executions of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and Robespierre illustrate its power to alter political landscapes, while reflecting the contradictions of its era. An archaeological analysis of the guillotine reveals not only the history of an execution device but also the values, conflicts, and aspirations of the societies that employed it.

Post a Comment